I must have been about twelve[1]. In front of me stood a wall of books, all the same size, racked so that their covers were facing me – no spines, just covers. And what covers! These were Panther Science Fiction novels, of the early 70s, and Panther's house artist was the great Chris Foss.

Back in those days, my parents would seek out the rainiest, most miserable corners of Britain for our annual vacation. That year, they had chosen a static caravan park in Fairbourne, a small holiday resort on the Snowdonian coast, across the river from the slightly larger metropolis of Barmouth (current population ~2,100); this after several years where we had spent our annual vacation on Yorkshire's east coast. Fairbourne was very much more of the same. Apart from the caravan, which was an innovation we never repeated.

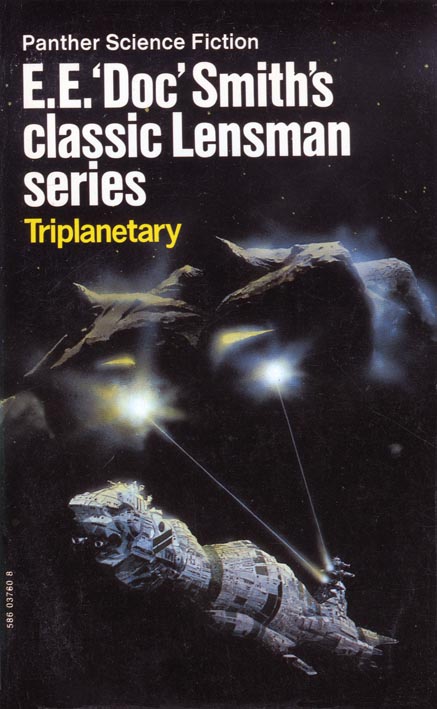

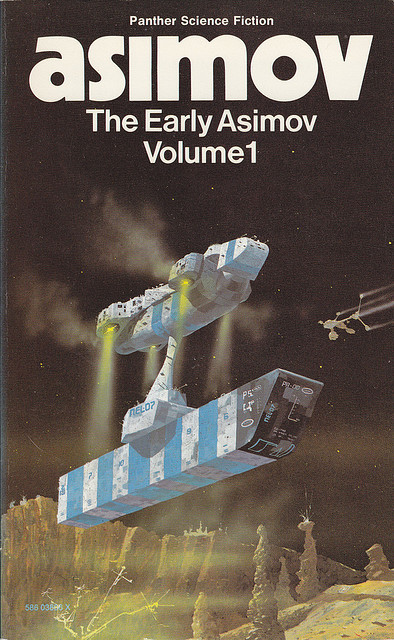

I spent a long time poring over them (Dad would take a daily constitutional to buy cigarettes; I'd scamper after him in the hope of another sight of those covers). The books I particularly recall include the whole of E. E. 'Doc' Smith's Lensman series. And a lot of Asimov. There were also some of the blue, textured, Corgi SF Collectors Library volumes (Corgi probably had a better set of writers – Arthur C Clarke, Brian Aldiss, various books that would now be considered classics – but they didn't have Chris Foss).

At some point, we were allowed to buy a book each. By that time, I had memorised the entire plot of the Lensman saga by reading the blurbs on the back. Nevertheless, I bought Smith's Triplanetary; my brother chose The Early Asimov, Volume 1. Back in the caravan, sheltered from the endless Welsh rain, I learned of the eternal war between the races of Arisia and Eddore, of the destruction of Earth's first civilisations, and of the plan by Arisian scientists to develop over time the ultimate weapon of the forces of good, the Lensmen[2]. And that was the start of my love affair with the future, one that continues to this day.

In the early days, my pocket money went on the covers. Chris Foss was renowned for not really having read the books he illustrated[3] – he admitted to it in his collection, Hardware[4]; he also pointed out, probably correctly, that the covers sold the books. Hardware's interior title page contains a photograph of a shelf of books with Chris' covers. It pretty much coincides with my early book collection: the rest of the Lensman series, James Blish, Perry Rhodan (the first ten, anyhow), more Asimov, A. E. Van Vogt, Ben Bova's set of Novella collections.

A year or so after Fairbourne, I found myself in a bookshop in York with money in my pocket and time to kill. I spent my lunch money on three paperbacks – The Forever War, The Left Hand of Darkness, and Clans of the Alphane Moon – and went hungry. That day, I got lucky: two of those books are now considered masterpieces, and the third is at least interesting. I tell the full story elsewhere; the short version is that my sense of discernment began to improve. I started paying attention to awards, to authors, to the names on the spines as well as the covers.

I've been meaning to write about these books for years. I finally got around to it.

The plan, such as it is: go through the Gollancz SF (and Fantasy) Masterworks imprints, using them as the main road, but also take detours to new books, recent books, and books which should be on the main road but aren't. The Masterworks list is a useful spine, not holy writ. And, along with the reviews and reminiscences about the books, you'll find some material on the cover art as well. Because I still appreciate the covers, even though grown-up me has learned to look slightly beyond them when buying a book.

Which is, of course, the Golden Age of Science Fiction ↩︎

That having been said, apart from Smith's spectacular prologue – in which the entirety of human history is attributed the cosmic struggle between Arisia and Eddore – the Asimov is a far, far better read. ↩︎

In fact, that UK Triplanetary cover was sufficiently generic that it was also used: in America, for Four for Tomorrow by Roger Zelazny; in France, for Planets for Sale by A. E. Van Vogt; and in the Netherlands, for The Lifeship (aka Lifeboat), by Harry Harrison and Gordon Dickson. I've probably missed some. ↩︎

Member discussion